Freely adapted from Beuys: Every person is a drawer

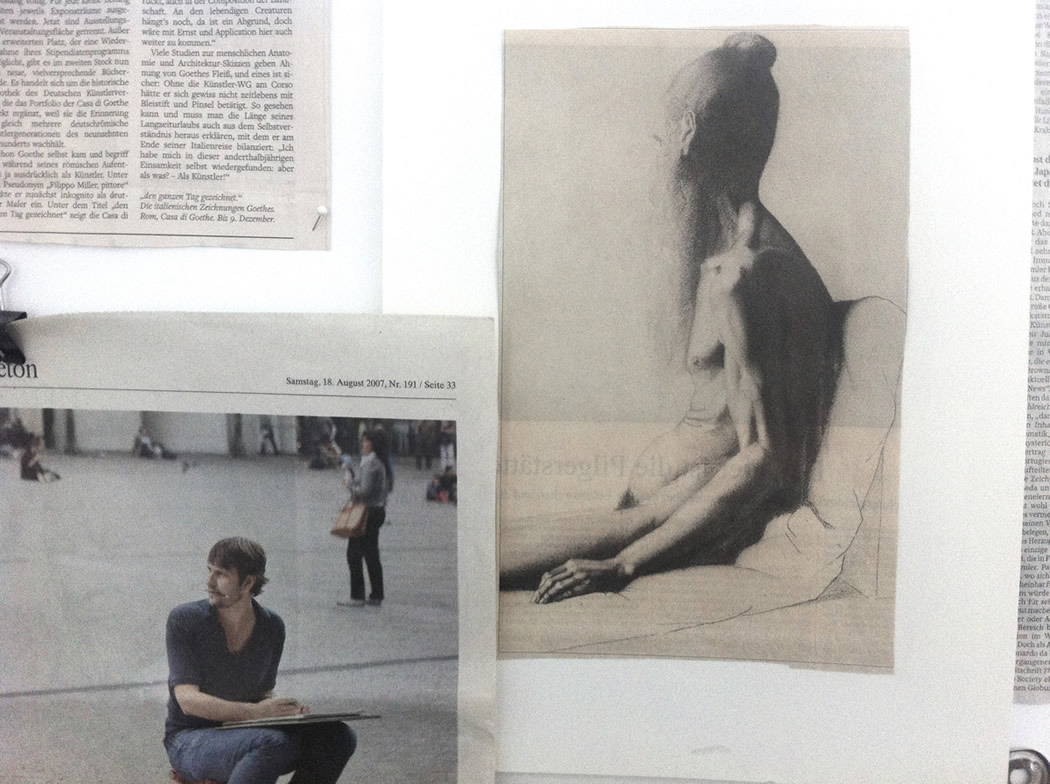

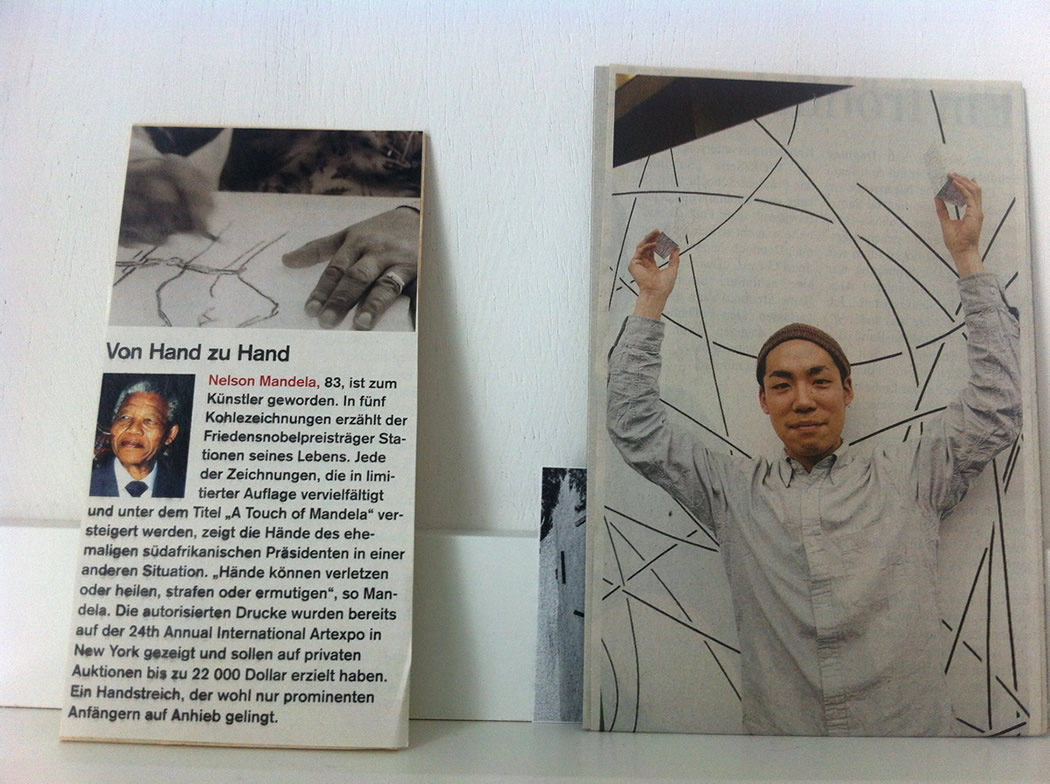

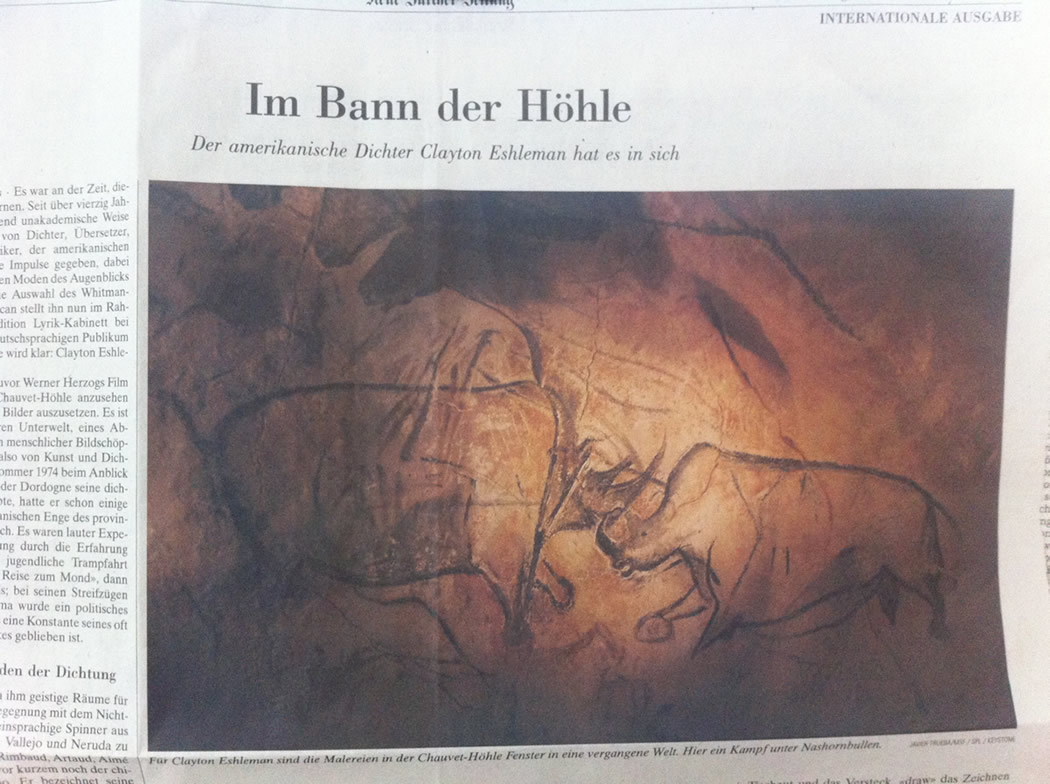

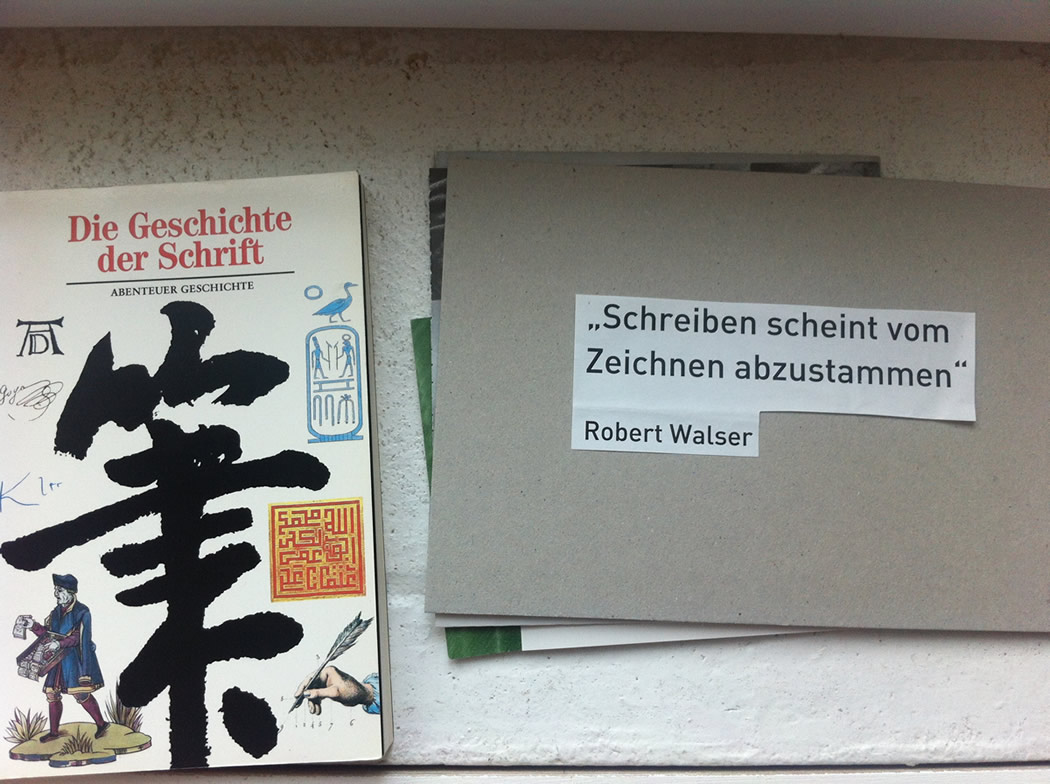

We begin drawing in early childhood. Drawing and writing by hand are everyday occurrences, or at least this has been the case up to now, a form of communication, a path from inside to outside. Handwriting and drawing by hand are indicators of each person’s uniqueness. The Museum for Drawing takes up the entire breadth and scope of the subject, from rock drawings and great art, down to telephone scribbles, tattoos and notes giving directions. It raises questions as to why we draw, from anthropological, philosophical, and artistic points of view. Drawn lines point beyond one’s own limits, beyond one’s own existence, and form an extension of the person who draws into other spaces. To explore and introduce this is the mission of the Museum for Drawing.

What is new?

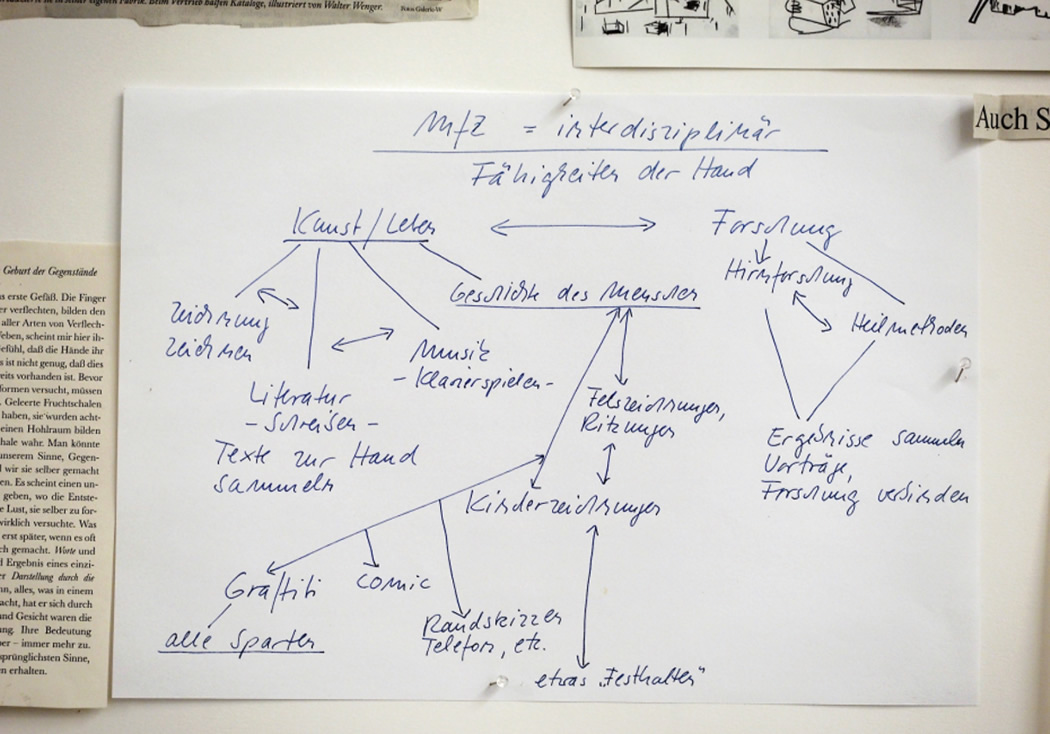

The Museum for Drawing is a museum that does not differentiate between the arts, everyday life, or the various fields of scientific research. Many of the themes are worked up on an interdisciplinary level in discussions, lectures, texts, or symposiums. Depending on the exhibition location and emphasis of the host museum, the selection and compilation will change with respect to the material exhibited. The Museum for Drawing disposes over its own collection. This consists largely of printed and copied materials, which means that there is no need to take into consideration any conservational restrictions, size differences, or the lack of a work’s availability. These reproductions do not replace the originals but instead, reference them. People may take them into their hands. The collection grows according to subjective criteria indebted to notions of playfully treating the material. Playing with cross-references and relationships leads to subjectively and intuitively motivated combinations on the wall panels.

This museum is not restricted to any one location. It disposes over its own exhibition furnishings that are easy to transport, consisting of panels with small shelves designed for leaning against the wall, tables, stools, display cases, and a filing cabinet. It is a museum that does not differentiate between the arts, everyday life, or the various fields of scientific research. Many of the themes are worked up on an interdisciplinary level in discussions, lectures, texts, or symposiums. The Museum for Drawing disposes over its own collection. For the most part, however, it consists of printed and copied materials, which means that there is no need to consider conservational restrictions, size differences, or the lack of a work’s availability. These reproductions do not replace the originals but instead, reference them. People may take them into their hands. The collection grows according to subjective criteria and is designed with the playful treatment of the material in mind. Playing on cross-references and relationships leads to subjectively and intuitively motivated combinations on the wall panels.

Depending on the exhibition location and emphasis of the host institution, the selection and compilation will change with respect to the material exhibited. It is no problem to include original exhibition pieces from the respective host museum, as was the case at Kolumba, or to integrate our Museum into hangings that already exist. A pencil and piece of paper would suffice, simple materials that are readily available. A line, drawn straight, then to the left, then the traffic light, the person who wants to give directions limits himself to what is essential, abstracting from the multitude of images and notions and leaving behind abstract traces. Depending on the person who describes the way, these traces are sometimes drawn hesitantly and tentatively, sometimes they are clear and lively, the linear traces show the energy of the person drawing, reflecting this at a particular moment in time and firmly recording it visually. No retouching, or whitewashing, something stands there on the sheet of paper and reveals more than the directions given. These small drawings reflect the directness, reduction, and abstraction to what is essential. Drawing and writing are closely connected with the developmental history of mankind. The story of drawing began with the first cave and wall drawings and scratchings 75,000 years ago.